Rising Impact, Rising Pushback

Third Party Litigation Funding (TPFL) is increasing litigation costs, settlement amounts and ‘nuclear verdicts.’ As insurers and defense counsel struggle to contain the results, legislatures are becoming involved.

Introduction

Not every potential plaintiff can afford to fund their living expenses through the life of their claim, and not every attorney can afford to meet payroll while litigation is ongoing. Plaintiffs shouldn’t have to settle for low-ball amounts or 3rd rate attorneys.

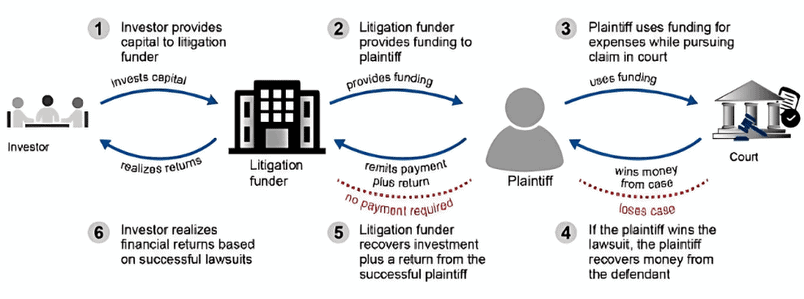

Enter the third-party funder, willing to provide the working capital needed in return for a share of future recoveries.

Consumer funding for living expenses during a personal injury case usually involves a loan of up to 10% of the estimated claim value. If the plaintiff loses, the loan is forgiven. If the plaintiff wins, they pay back the original amount and a return, which can be an interest rate, a multiple of the original advance or a pre-negotiated share of the recovery.

Commercial funding (for corporate plaintiffs and/or their attorneys in commercial actions) may involve loans in the millions of dollars, and agreements may involve a single case, or a portfolio arrangement, where a law firm or business obtains funding in exchange for a share of the value of several cases. Funds can be used for any costs during litigation. Law firm funding demand is being driven by rising advertising costs, increased investments in data and analytics, and more mock trials.

Source: U.S. Government Accountability Office

Litigation funders include specialist legal claim companies who source capital from endowments and pension funds, traditional multi strategy hedge funds (with dedicated litigation finance desks), and high net worth individuals, family offices and hedge funds (without dedicated litigation finance desks).

Concerns

TPLF increases the cost of litigation – by encouraging frivolous lawsuits, prolonging discovery (including disclosure motions around the funding) and extending case timelines.

TPLF increases settlement amounts – consumer TPLF interest rates may range from 15% up to 124%. These rates may force plaintiffs to reject reasonable settlements, since funders are paid first, and may leave little for the plaintiff who actually suffered injury. Not every consumer understands the compounding effect of high interest rates: one litigant received an $18,000 advance and owed $33,000 to the funder six months later. Another plaintiff borrowed $27,000 to pursue a ‘slip and fall’ case which settled. After the funder took almost $100,000 and attorney fees were paid, the plaintiff was left with $111.

In 2016, plaintiffs received 55% of compensation paid in the commercial liability tort system. However, where TPLF was involved, that figure dropped to 43%. A plaintiff using TPLF would need to receive a 27% higher award to receive the same payment as one not doing so.

TPLF drives nuclear verdicts – TPLF agreements impact claims, with longer, drawn-out cases and more plaintiffs holding out for jackpot jury awards. This contradicts the premise that cases are litigated as efficiently as possible, to settle at the fairest value. TPLF also enables law firms to advertise widely and suggest lottery-sized verdicts are normal (they are not).

Portfolio funding bankrolls a portion of a firm’s cases in exchange for a share of the proceeds. Spreading the risk makes sense for the funders: it reduces the risk of pursuing questionable claims for a potential financial windfall. Additionally, the funder’s goal of maximizing profits may conflict with a plaintiff’s desire to accept a reasonable settlement. Some funding agreements allow funders to control the plaintiff’s ability to settle, and funders are willing to risk that a plaintiff receives nothing in exchange for the potential of a nuclear verdict.

TPFL may allow foreign entities to (adversely) impact American companies – sovereign wealth funds and others may invest in ways that potentially harm US companies.

Disclosure

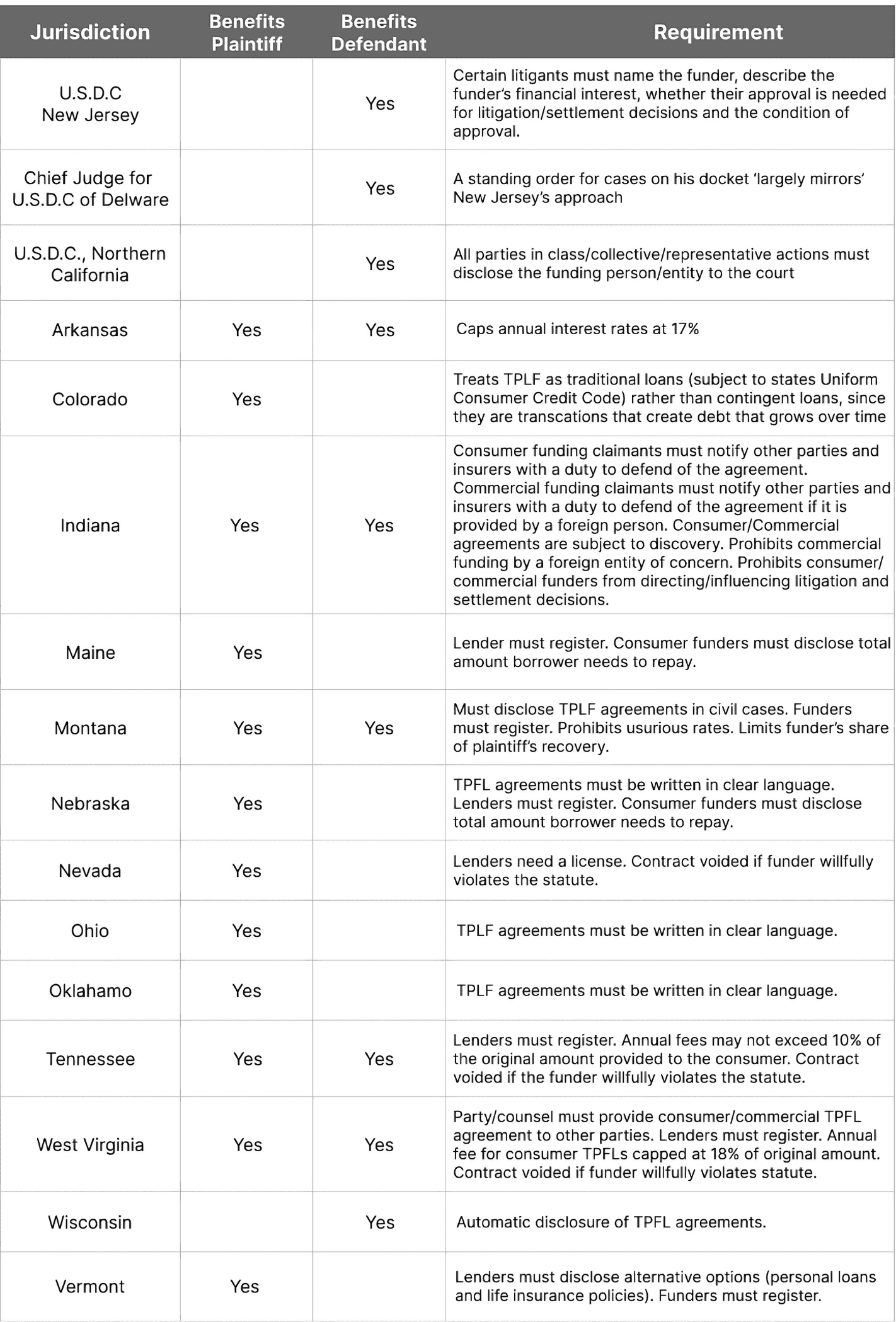

Plaintiffs and funders prefer to keep quiet about TPLFs. Some jurisdictions are taking steps to improve transparency and apply consumer protections:

For cases involving TPLF agreements, consider the following steps:

1. Educate the court on why disclosure is material (to facilitate settlements and allow defendants to see who controls the litigation/settlement discussions). TPLF agreements should be discoverable, because it gives funder’s a financial interest that accrues over time.

2. Argue that in New York TPLF agreements executed after liability is established are loans subject to NY’s usury statutes.

3. Seek to compel funders to appear for court-ordered settlement conferences, to enable direct negotiations and to change the optics (true adversary is a hedge fund/sovereign wealth fund).

What’s Next?

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce Institute for Legal Reform has asked Congress for a federal statutory disclosure requirement to improve transparency and expose potential conflicts of interest and/or violations of laws preventing non-parties from funding litigation.

Third party litigation funding is a multi-billion dollar industry (over $15 billion of assets under management of funders who finance US commercial lawsuits). Latest developments include a secondary market to enable funders to sell parts of a portfolio to free up liquidity or to exit positions.

If you don’t know about the funding agreement, you may not anticipate (or reserve) sufficiently for the outcome.

Perich, M. Bloomberg Law, Profile of Litigation Funders, January 3, 2024.

Consumers for Fair Legal Funding, as of March 25, 2024.

Davis, R (2023). Litigation Funding What Insurers Need to Watch. The Conning Commentary Strategic Issues for Insurance Industry Executives

Abraham, H. & Graham, M. New York’s Unregulated Litigation Lending Industry, October 13, 2023.

The Westfleet Insider: Westfleet Advisors 2023 Litigation Finance Market Report.

Lula, J. Five Litigation Funding Trends to Note in 2024, January 10, 2024.

CONTACT

If you have any questions or are interested in learning more about this topic, please contact Frank DeMento (fdemento@transre.com) or Howard Freeman (hfreeman@transre.com).

DISCLAIMER: The material contained in this memorandum has been prepared by Transatlantic Reinsurance Company (“TransRe”) and is the opinion of the authors, and not necessarily that of TransRe. It does not, and is not intended to, constitute legal advice and is for general informational purposes only. All information is provided in good faith, however TransRe makes no representation or warranty of any kind, express or implied, regarding the accuracy, adequacy, validity, reliability, or completeness of the information provided. This memorandum is the confidential and proprietary work product of TransRe and is not to be distributed to any third party without the written consent of TransRe.